The Fe(Male) Gaze in Modern Cinema

How the gender binary affects what we see and how we feel about it.

In the rich, yet storied history of visual arts and media, there is an age-old tradition that has been held up in the film industry for over a hundred years: The Male Director. This tendency is so apparent, in fact, that the “language” of film theory and filmmaking has a phrase for what exactly happens when men are the majority behind the camera. That phrase is “the male gaze.”

Coined by Laura Mulvey in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” the term describes the roles in which women inhabit and inherit within films and their passive and sexualized nature.

But First, A Brief History Lesson

The Male gaze wasn’t coined by Mulvey until the 1970s, but it’s not as if it just didn’t exist before then. Historically in narrative filmmaking of any age, men have been more likely to be involved in the telling of stories, and this is especially true in Hollywood cinema.

Throughout the 20th Century, the Hollywood studio system went through countless changes in power, but it and its production hit a peak in the 1920s through the 1940s. This is when many films that created what we see now as the dominant male gaze were produced, directed, and distributed by almost exclusively cis, straight, white men. Due to the lack of independent productions, the studio system dominated production of almost all films. When a very small, tight-knit group of people are running almost all production of films throughout more than 2 decades, they tend to hire who they know and trust. If that group in charge consists of men, then they will most-likely hire men. It is not entirely known if that is what caused women to lose footing in the industry at this time, but it can be suggested due to the data.

After the Hollywood studio system collapsed, more women were encouraged and hired to make their own films, but the industry is still dominated by the same side of the binary to this day.

So how do we change that? Can we remedy it just by adding diversity within the industry? Slowly but surely, I think we can.

The Male Gaze (as Mulvey sees it)

Coined by Mulvey to describe what is known as the “power to look,” the male gaze is widely understood in cinema. In film specifically, due to the gender imbalance within the industry and the power of the patriarchy, the male gaze represents how women were (and are) portrayed in Hollywood Cinema through a male perspective.

There are three main “gazes” in filmmaking that obstruct our own understanding of characters in any media we see.

The first one is the look of the camera in the situation being filmed (Pro-filmic event). This look is inherently voyeuristic and traditionally male due to the history of male directors in the industry. This gives the camera a powerful, voyeuristic, and male-centered view over most of the media we see, continuing the objectification and passivity of women just by way of the actual act of filming.

The second look, the one of the usually male protagonist within the narrative, is what does the passive objectifying of women in the film itself. This look is perpetuated by the industry-standard of writing and portraying male main characters and giving them active parts within narratives. We see this in the obvious examples, like almost every superhero movie and every category of action film, but we also see it within women-centric genres like some romantic comedies and dramas. It was ever-present throughout the golden age of cinema and continues into the new age as well.

Last but not least is the third look, the one of the male spectator, which often imitates the first two. This is due to the language of cinema, the way in which it is constructed, and the influence it has over the people who consume it regularly. Even if a spectator is not a cis male, they will consume the media through the same two lenses (or looks) as the male audience member, because the first two looks are so dominated by one side of the binary.

This is the basis of Mulvey’s concept and theory, and it is what the idea of the “female gaze” sets out to demolish.

But, according to Eileen McGarry, “reality is being coded before the filmmaker arrives so that she, in fact, is dealing with the pro-filmic event: that which exists and happens in front of the camera.” Because of the history of cinema and the language that already exists around filmmaking and what we show in front of the camera, women are dealing with a previously understood gaze in which anyone that has consumed film before already understands. Her job, then, is to deconstruct such looks and change the narrative. (Dirse, 18).

The Female Gaze

Although it might sound as though the female gaze is just the opposite of the standard male gaze, and if we just started putting men in the objectified and sexualized roles and women in the active roles as protagonists, then the problem would be solved.

It is, unfortunately, not that simple.

The female gaze is complicated by the history of cinema and how the camera has been used for a century, but it can be described as the right of women to adopt the active and objectifying gaze that has traditionally been associated with men, undermining the dominating cultural alignment of masculinity with activity and femininity with passivity.

Stated above, there are three sets of eyes a film is typically catering to: the director, the protagonist, and the spectator. When all of them are assumed male, then the way everything within the film is projected is skewed, favoring one side of the gender binary. This is how we have cultivated a culture of objectification.

Joey Soloway said in a keynote address for TIFF in 2016 that “the female gaze is a conscious effort to create empathy as a political tool. It is a resting away of the point of view.” It is not simply something that only cis women can do, either.

Anyone aware enough of the trapped nature of femininity within the cinematic lens can construct a new point of view for any femme-presenting character in any film. This will, in theory, free others from the staunch grasp that cis men have held over women in this industry.

It is more common to see the male gaze in cinema, due to the overwhelming disenfranchisement of women in the industry. When men are encouraged to write and direct stories, they often display women as objects, things to be desired by their straight cis male counterparts, and that is how the sexualization of women is perpetuated over a century of filmmaking.

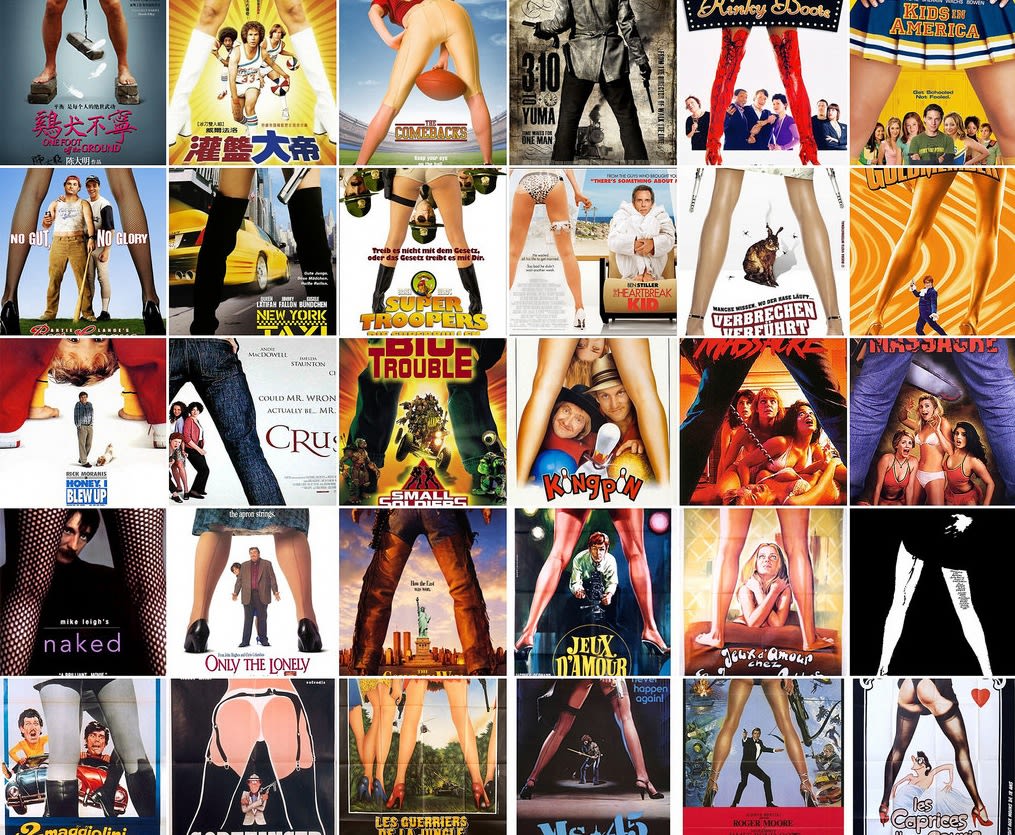

Here are some examples:

In Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) Jimmy Stewart can be seen following (let’s be honest, he’s stalking) Kim Novak’s Madeleine Elster throughout her very mysterious days. This example of the male gaze is widely disputed, so I will just touch on Stewert’s character Scottie to explain. He falls in love with Madeleine basically at first sight, creates this image of who she is in his mind, and becomes obsessed with the thought of her. An image of a woman he doesn’t know, created in his mind as the perfect woman for him. This is shown through really meticulous shots of Madeleine within the first hour of the film. Though Hitchcock is known for objectifying and ultimately killing the women in his films, he puts a certain twist in this one that will leave you speechless. Though she is strong and complicated, she is still the object of Scottie’s eye and her storyline revolves around his love for her, or at least who he thinks she is.

In Michael Bay’s Transformers (2007), the director introduces Megan Fox’s character Mikaela Banes with a sweeping shot that isolates her body as she peaks underneath the hood of a car. Concentrating on her exposed midriff and body in the beautiful golden-hour lighting does nothing to move the story forward. This shot isn’t used to explain something about the character or to reveal her important characteristics as part of the story. It’s only use is to show the male protagonist’s point-of-view and to explain his innate attraction to her and how much she knows about cars. This is possible through Bay’s famously chaotic directing style and his obsession with useless female characters that only fulfill the protagonist’s wishes.

These examples explain both the first look and the second look, but what about the third?

Well, the answer lies in the eye of the beholder, or in this case, the audience member. The objectification of women lies in every off-hand comment about how hot Margot Robbie is in The Wolf of Wall Street, but now how nuanced and layered she is as Tonya Harding in I, Tonya. She is so often seen as just a pretty face and not a person, and that is where the objectification lives. This stems from what we see in the movies.

How We Perceive

In filmmaking, perception is often talked about when explaining the pleasure and joy that we can receive from watching movies. We become voyeurs, something Hitchcock was so obsessed about that he made most of his films about it, and it is precisely why the male gaze works. When watching a film, we are steered toward the point of view of the protagonist. When this character is most often a cis straight male, the characters opposite are most likely cis straight women. The woman is often seen as a prize to be won, so often that there are whole genres dedicated to exploring this.

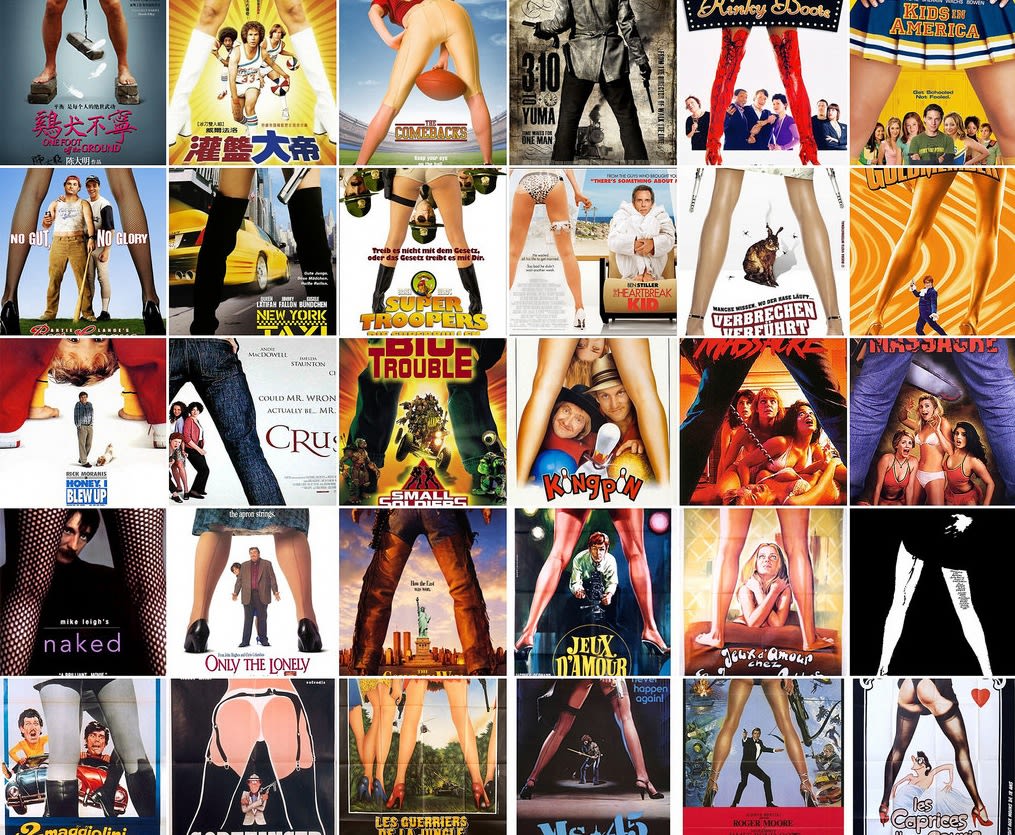

Male Gaze

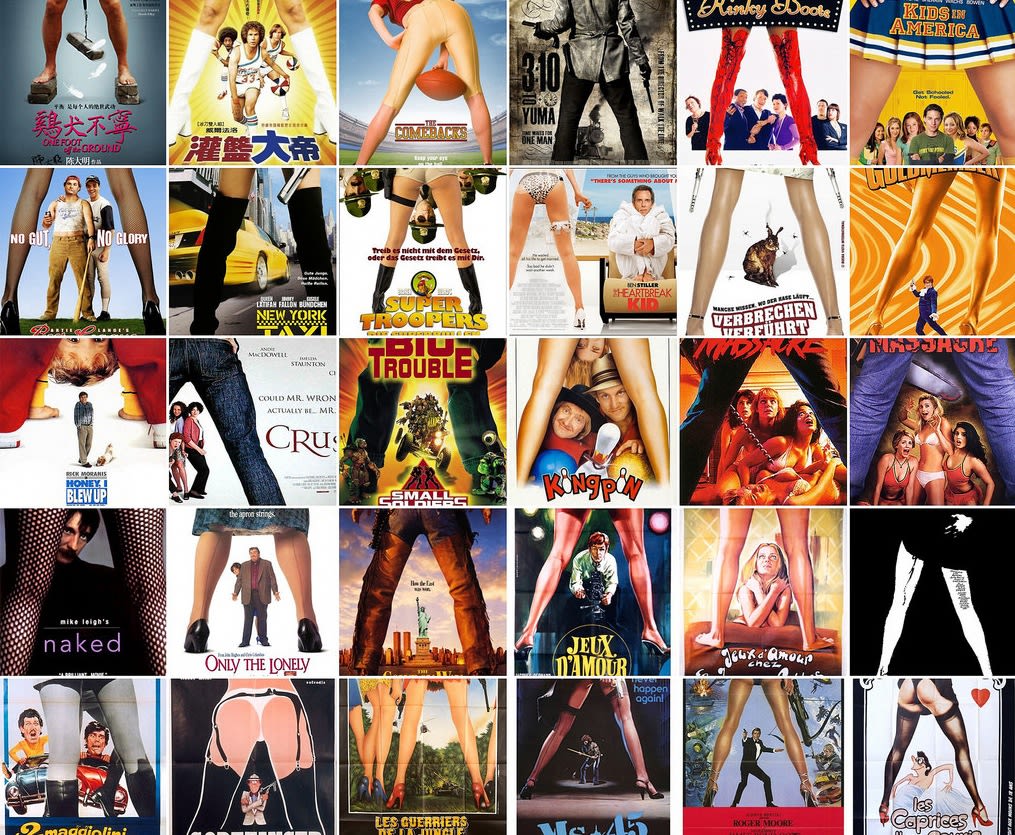

Female Gaze

Why does this matter?

The obvious solution to this tendency in cinema would be to hire more women directors, writers, actors, producers, etc, but will that solve the issue? The history of cinema has embedded in every single person that consumes it that women are to be objectified, sexualized, and in many cases far worse things. That is the space they inhabit on our screens, and the longer it continues, the longer women in the real world see themselves as just the same. If we are taught through visual media, the closest form of art relating to reality, that women are all the same, one-note, sexual beings made in a lab for cis men to consume for themselves, then we eventually start to believe it.

"Mulvey's ideas are based on difference theory, the premise being that there is an inherent difference between the sexes. Her concept of three looks, or gazes, helped to establish the debate. In the past two decades, these three looks have been radically redefined as gender, race, and ethnicity enter the equation and new modes of interpretation are necessary in order to evaluate the gaze."

The Concept of Feminine

Dirse continues on saying the following:

"Helene Cixous'o and Luce Irigarayn developed theories related to ecriture feminine, a "feminine" writing whereby gender gains entry to culture through an embodied difference rather than a historical context. Ecriture feminine provided a link between theories of sexual difference and theories of deconstruction (Derrida's method of textual analysis based on the premise that there is no "reality" unmediated by discourse). Hence binary notions in language - such as man/woman and Black/White - are not immutable but constructed oppositional pairs. Rosemarie Buikema explains that "the consequence of deconstructive thought for feminist theory is that femininity is disconnected from a specific female identity. Femininity can be regarded as a discursive construction and not as exclusively related to a specific biological social group. An insight into the way in which positions of power are distributed in texts between masculine and feminine, and/or between white and black, can be a forceful instrument in the struggle against the one-sided and/or equivocal representation of femininity."

Since the deconstruction of the gender binary is a new topic for some, and very rarely talked about in mainstream cinema, the topic is not very researched. Queer cinema exists, that's for certain, but their deconstruction of the gazes is far more complicated and not as talked about, but I must mention quickly that gender is a construct and this examination of the male and female gazes is inherently flawed. Since there is a dominance of cis, straight men in Hollywood, however, it is still relevant and happening.

Percentages of Best Picture Oscar-Winning Films that pass the Bechdel Test.

Female Directors, 2019

What Does the Female Gaze Look Like?

Chantal Akerman's Jeanne Dielman...

Chantal Akerman’s 1975 classic Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels famously shows a housewife in a collection of static-framed long shots as she goes about her mundane and repetitive life. She prepares meals, talks to her teenage son, and entertains three men as a sex worker. We, the audience, do not see much of the sexual relations, something that we would see much more of if Akerman were seeking to sexualize her for a male audience. Instead, we are told by the repetition that Jeanne is not content in her life, that she seeks more for herself, and she eventually goes after it.

She is liberated in her control over her own narrative, and that is directly possible because of the filming techniques that Akerman used. She used her own found control over the first look in order to ensure Jeanne would be seen in a particular way, gaining more control over the other two looks in the process, and created a feminist portrayal of a women burried by circumstance that figures out a way to gain back her own control over her body and its narrative.

A result of third-wave feminism and the influence of totalitarianism, Jeanne Dielman lives in a certain era of filmmaking that we are still theorizing about to this day.

Since 1975, there has been a wide range of films that could be considered shot and performed with the female gaze in mind, and one I find particularly interesting is Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird (2017).

It follows, quite simply, a girl and her mom’s relationship as she grows up out of a rocky adolescence into an early adulthood. An age where so many other characters that came before her have been sexualized and degraded just for being teenage girls, (think Thirteen, American Beauty, The Virgin Suicides, etc) Gerwig assures that Lady Bird stays on neutral ground.

Though we see a relationship form between her and an eligible high school boy, she is never shown in parts like other characters before her. She is shown as a whole person, with feelings, emotions, connections with friends and family, staunch beliefs and wishes for herself, and her own strong and independent self awareness that can only be shown if the creator is aware of harmful tropes thrown onto teenage girls in the visual arts.

A more recent example of a liberated female gaze can be found in Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019).

In the film, young painter Marianne travels to an island in Brittany in 1770 to paint a wedding portrait of reluctant wife-to-be Heloise. The painter must observe her on walks in order to paint her likeness by memory in secret, since Heloise will not sit for a portrait. She does not want to get married off, but has no choice in the matter. In the film, we see the two young women fall in love in the process and after Heloise finds out that Marianne was commissioned to paint her, she decides to sit for her.

Filmed almost entirely from the perspective of Marianne, we see Heloise in stolen glances and concentrated angles, never sexualizing her until the two characters are lovers. The difference between sexualizing women in the male gaze and the female gaze has to do with who is watching her. Marianne sees her as an equal, a partner in a world that does not accept their kind of love. In a world where they could never end up together, they find love in elongated glances and silent moments together.

Sciamma takes great care in the framing of both women in this film to ensure that their love story is at the forefront and though the characters are sexual creatures, it is only shown in enlightening ways where the characters themselves are in control of what we see and how we see it.

That is what I find to be the female gaze at its finest and most profound.

So What?

Does this answer any questions or revolutionize the industry in any way? In my eyes, and in the eyes of Joey Soloway, the female gaze is a regrasping of a type of narrative that has been skewed for decades in the wrong direction.

It is a chance for femme presenting people to be portrayed in the same light that masc presenting people have always been shown.

The feminine is allowed its day in the sun when people consider the female gaze in order to demolish the male influence that has come before it. With it, we can restructure stories around women and overt femininity without sexualizing them for male eyes only.

The female gaze is a strong decision to show femmes as protagonists, for sure, but also as decision makers, heroes, lovers, daughters, mothers, artists, anyone. It gives a little bit of the control back to the neglected side of the binary, and we have much further to go in order for everyone’s voices to be heard.

What You Can Do

First and foremost, watch films made by people that do not identify as cis white men. It’s that simple. Find other media that portrays people in clear ways, directed by people that look like their characters. Question the visual media you have most likely grown up on and ask yourself if the women pictured are ever neutral, or god forebid non-sexual, and how those characters are portrayed if so. Make an effort to expand your own horizons as a viewer and more complicated and nuanced narrative will find you. Maybe in the end, we can close a couple of gaps along the way.

Thank You!

Sources:

Akerman, Chantal, director. Jeanne Dielman: 23, Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. New Yorker Films, 1975.

Bay, Michael. Transformers. Paramount Pictures, 2007.

Dirse, Zoe. Gender in Cinematography: Female Gaze (Eye) behind the Camera,

Ferrier, Aimee. “10 Incredible Films That Question the Male Gaze.” Far Out Magazine, 7 Mar. 2022, https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/10-incredible-films-that-question-the-male-gaze/.

Gerwig, Greta, director. Lady Bird. Universal Studios, 2018.

Hitchcock, Alfred, director. Vertigo. Paramount Pictures Corp., 1958.

“Joey Soloway on The Female Gaze.” Performance by Joey Soloway, YouTube, YouTube, 11 Sept. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnBvppooD9I. Accessed 6 Nov. 2022.

Mulvey, L. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6–18., https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6.

Oliver, Kelly. “The Male Gaze Is More Relevant, and More Dangerous, than Ever.” New Review of Film and Television Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, 12 Oct. 2017, pp. 451–455., https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2017.1377937.

Sassatelli, Roberta. “Interview with Laura Mulvey.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 28, no. 5, 2011, pp. 123–143., https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276411398278.

Schneider, Maggie. “Seeing You Seeing Me: The Female Gaze in Cinema.” The Science Survey, Wordpress, 2022, https://thesciencesurvey.com/arts-entertainment/2022/03/16/seeing-you-seeing-me-the-female-gaze-in-cinema/.

Sciamma, Celine, director. A Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Camera Film, 2019.

Stefanovic, Patricia, and Ana Gruić Parać. “Male Gaze and Visual Pleasure in Laura Mulvey.” The Palgrave Handbook of Image Studies, 2021, pp. 343–362., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71830-5_21.